Who's In Charge Here?

Read John 19:1-16.

Who is in charge here? That's a question we sometimes ask in light of squabbling politicians and policies that never seem to go anywhere. Our government has checks and balances built in, which is a good thing, but it sometimes makes it difficult to know who is in charge. Who's making the real decisions—or who is supposed to?

Even when clear authority is established, we've been taught to question it. Social media has given us the power to voice our opinion, well-considered or not, and to demand our...well, we call them "rights" but very often they are merely preferences. Who's in charge here? Who has authority?

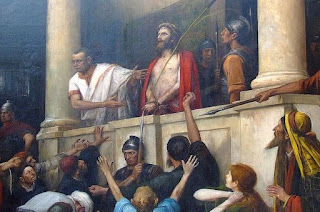

The scene we read in John's Gospel today has that same sort of question hanging over it. Who's in charge here? Everyone seems to think they are, but no one who thinks that actually has any sort of real power. Think about the characters in this drama: Pilate is the appointed Roman governor, and he has all the might and power and authority of Caesar backing him. He says he has the power of life and death over everyone in the province of Palestine, including Jesus (19:10).

The chief priests are the appointed religious and spiritual leaders of the people. (Think "senior pastors.") They are used to people responding to their direction and seeking their advice. In some ways, they were understood to possess the power of spiritual life and death over everyone in the province.

Then, there are the soldiers. Yes, they are flunkies or employees of the Roman Empire and as such, they are at Pilate's disposal. But John says they "took charge" of Jesus at the end. Before this, they have ridiculed him and shamed him and tried to provoke some violent response. They believe they have the power of fear and shame and torture over anyone in the province.

And then there's Jesus. We often say he was "beaten and bruised," but that is a sanitized version of what he looks like by now. He has been a rabbi, a traveling teacher, who had gained a modest following (though by now, a lot of people considered themselves "former followers of Jesus"), but now he is a shadow of the man he once was. He has been flogged, and a Roman flogging was not finished until the flesh was shredded and hanging from the victim's body. He is a pathetic figure at this point, undoubtedly with little strength left to stand, let alone speak.

Yet, Jesus is the one with the authority here. He himself says it this way: "You would have no power over me if it were not given to you from above" (19:17). Though he says it to Pilate, the statement applies equally to anyone else involved in this story. The only power they have is what God the Father has allowed them to have so that this divine drama of salvation can play out. Jesus isn't a victim here. Jesus is in charge, and he is willingly offering himself for the sake of the world.

Who's in charge here? Jesus is—then and now. Is he in charge in your life, or do you think you are?

Who is in charge here? That's a question we sometimes ask in light of squabbling politicians and policies that never seem to go anywhere. Our government has checks and balances built in, which is a good thing, but it sometimes makes it difficult to know who is in charge. Who's making the real decisions—or who is supposed to?

Even when clear authority is established, we've been taught to question it. Social media has given us the power to voice our opinion, well-considered or not, and to demand our...well, we call them "rights" but very often they are merely preferences. Who's in charge here? Who has authority?

The scene we read in John's Gospel today has that same sort of question hanging over it. Who's in charge here? Everyone seems to think they are, but no one who thinks that actually has any sort of real power. Think about the characters in this drama: Pilate is the appointed Roman governor, and he has all the might and power and authority of Caesar backing him. He says he has the power of life and death over everyone in the province of Palestine, including Jesus (19:10).

The chief priests are the appointed religious and spiritual leaders of the people. (Think "senior pastors.") They are used to people responding to their direction and seeking their advice. In some ways, they were understood to possess the power of spiritual life and death over everyone in the province.

Then, there are the soldiers. Yes, they are flunkies or employees of the Roman Empire and as such, they are at Pilate's disposal. But John says they "took charge" of Jesus at the end. Before this, they have ridiculed him and shamed him and tried to provoke some violent response. They believe they have the power of fear and shame and torture over anyone in the province.

And then there's Jesus. We often say he was "beaten and bruised," but that is a sanitized version of what he looks like by now. He has been a rabbi, a traveling teacher, who had gained a modest following (though by now, a lot of people considered themselves "former followers of Jesus"), but now he is a shadow of the man he once was. He has been flogged, and a Roman flogging was not finished until the flesh was shredded and hanging from the victim's body. He is a pathetic figure at this point, undoubtedly with little strength left to stand, let alone speak.

Yet, Jesus is the one with the authority here. He himself says it this way: "You would have no power over me if it were not given to you from above" (19:17). Though he says it to Pilate, the statement applies equally to anyone else involved in this story. The only power they have is what God the Father has allowed them to have so that this divine drama of salvation can play out. Jesus isn't a victim here. Jesus is in charge, and he is willingly offering himself for the sake of the world.

Who's in charge here? Jesus is—then and now. Is he in charge in your life, or do you think you are?

Comments

Post a Comment